An audiobook reading of this chapter is freely available here:

Windboy_chapter_4.mp3

"The fact that radio hasn't been discovered yet," I said, "Is bad news, because none of the components for building a radio receiver have been invented. But it's also good news, because it means we won't have to worry about picking up any artificial radio emissions. There'll only be natural emissions, like from the time-warp hurricane. So if I can build a radio detector, it doesn't need to tune in to any specific frequency."

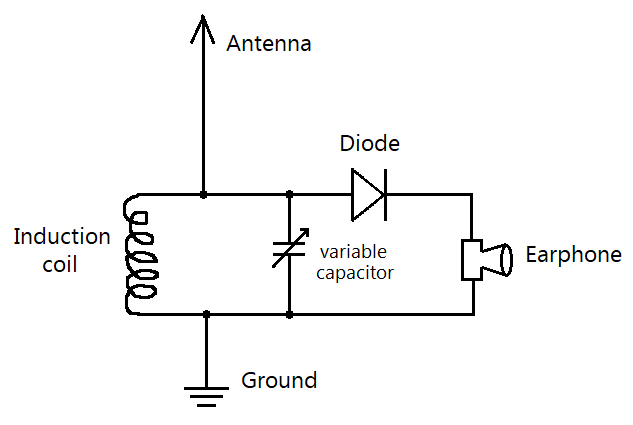

I scratched a schematic into the dirt with a twig. It was filled with lines and squiggles, odd symbols and side branches. It looked like this:

Windboy looked at my diagram with a mix of curiosity and bewilderment. "The simplest kind of radio is a crystal set," I explained. "It's powered entirely by the radio signal, and needs no batteries or electric generator. Now a normal crystal radio set requires a variable capacitor and an induction coil to tune in on any one frequency. Both of these components require precision engineering to get their capacitance and inductance exactly right, and I doubt I could build them in the two weeks we have to find your hurricane. But because we don't need tuning, we won't have to worry about building either of these."

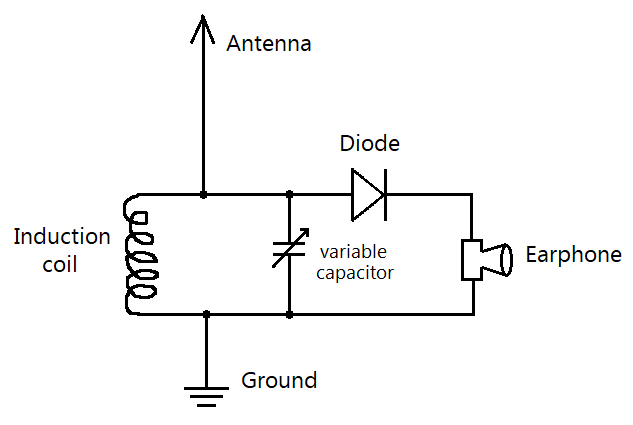

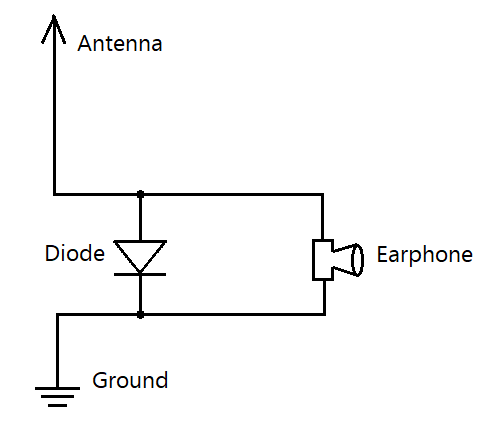

I rubbed out the symbols for the capacitor and inductor, and moved the diode where the capacitor used to be. Now, my diagram looked like this:

I continued: "Crystal radios also require a crystal, a semiconductor diode of some kind to rectify the signal. That's how they extract amplitude-modulated audio that's piggybacking on the carrier wave. I don't know if I could build a crystal diode, but good news there, too. The emissions from a time-warp hurricane are just pulses of radio noise. That means we won't need to worry about demodulation, so that should mean we don't need a diode either." I rubbed out the diode symbol from my schematic. "So there are just two problems remaining: detecting the signals seven centuries before the invention of the earphone, and determining where the radio bursts are coming from."

I frowned. Circuits, even without fancy components, still needed wires. Even something as simple as plain, uninsulated copper wire was going to take refined metals. I hoped that long thin strands of copper, or copper items that I could easily turn into long thin strands, were something the locals made.

"We're going to have to buy a lot of the raw materials," I said. I reached for my wallet. "I don't remember how much money I have with m—" Then I realized how stupid that was. "Never mind. I don't think anybody here is gonna take 20th century money." I looked over at Windboy. "You . . . don't happen to have any 12th century English money with you, do you?"

Windboy shook his head. "I can't really carry anything with me across a time-warp reset." He gestured to his costume. "I'm still not sure how I managed to keep this super hero outfit. But," he grinned, "I do happen to know where to find quite a bit of useful coinage. There's a chest loaded with silver pence stashed away in an obscure cave. I found it several visits ago, back when I was 8. If we take it, we won't be hurting anyone except the thieves who stole it. Let's go!"

The updrafts returned, along with the cold of the wind carrying me aloft. We can also use some of that money to buy a jacket for me, I thought. And maybe a decent meal.

Mercifully, the cave was only a quarter hour's flight away. That whole quarter hour was still as cold and precarious as each previous flight, though. I was shivering when we landed at the mouth of the cave. I asked Windboy, "How can you stand the cold from your own updrafts?"

"The fabric helps," he said, indicating his super hero costume. "It keeps out practically everything. I could fall in a lake and it wouldn't get wet. It hardly ever needs cleaning. That means it doesn't 'breathe,' though. On a hot day, it can trap the body heat of a normal person something fierce. A lot of the people who wear it in the 2500s put cooling units inside their clothes. Of course," he smirked, "I have my own ways of providing ventilation."

It also still fit him after a couple of years of growing up. One size fits all, perhaps?

Windboy pointed to the cave entrance. "Anyway, let's go in."

The cave wasn't very deep. There was still enough ambient light from the entrance to see the little coffer, once Windboy pulled it out from behind a small boulder. He opened it, and showed me the bulging leather coin sack inside. "Go on, hold 'em in your hand," he said.

"Uh, okay," I said, raising my eyebrows in half-surprise. I picked up the sack by its straps. For such a small thing, it was damn heavy — and it jingled.

"We'd better leave the cave before the thieves come back," Windboy said. I couldn't have agreed more. We scampered out, then trotted into a secluded wooded area nearby. It didn't look like anyone had seen us. Once it looked safe, we sat down and I opened the sack. The coins inside were the size of a quarter, but not as thick. A few were round and intact, but most of them had been cut in half, or even cut into four pieces. On one intact coin, I saw a crude likeness of a man wearing a crown and carrying a scepter. Scrawled in a long arc around his head were the words "hENRI REX".

"Henry the First," Windboy said. "He's been king of England for the last 27 years."

I hefted the coin in my hand. It felt awfully light. I took a dime out of my wallet — it was dated 1964, the last year dimes were still made out of silver — and compared the two coins. The dime was heavier. In 1967, the silver in this dime was worth about 15 or 20 cents, so this penny could probably buy about what a dime could buy in 1967. Assuming silver was as valuable in the 12th century as it was in the 20th, which might be a pretty big assumption. "I hope this is enough to buy everything we need," I said.

"It should be," Windboy said, "Unless you need to buy a plot of land or something. Tie that bag onto your belt, and I'll take you to a town I remember nearby. It's called Deftshire. There's a decent-sized marketplace there."

I looked to the west horizon. The sun was getting low. "Understand," I warned him, "That building a working radio receiver is going to take a while. Probably more than just a short afternoon. And I'm going to need a place to work on it that has a bench and good light, and is away from prying eyes, and has no wind so that my componets will stay put. No offense. That means we're gonna need a place to hole up for a few days. Oh, and I can't really work on an empty stomach. I'm gonna need something to eat first, and I'm guessing you're getting pretty hungry by now too. Er . . . you do eat, don't you? I mean, you don't just subsist on wind or something?"

Windboy rolled his eyes. "Of course I eat. And yeah, now that you mention it, I am getting pretty hungry. Okay, food and lodging will be our priority. Let's go!"

He blew both of us back into the sky — even now, I still struggled to keep my balance — and set us down a ways from the town. It would do us no good to have the locals see us swoop in from above. He walked me to the town's outskirts, then directly into an open-air market. We got a lot of looks. Windboy's super hero outfit was outlandish enough, but even my sweatshirt, denim jeans, and canvas sneakers stood out against the 12th century clothing everyone else had on.

Windboy approached a middle-aged woman selling various trinkets and household goods. She spoke a short sentence to him; or at least, I think it was a sentence. While her words sounded like they ought to be familiar, I couldn't understand a single thing she was saying. I was hearing medieval English, and it might as well have been a foreign language.

That's when Windboy did something I totally didn't expect. He opened his own mouth to speak, and the same incomprehensible language came out of him. And the vendor woman nodded in understanding, and replied! This ten-year-old boy, who'd travelled through time to God-knows-when, had somehow along the way managed to learn twelfth-century English.

He turned to me, and said, "She says there's an inn down the street here where we can rent room and board."

"I thought you'd only visited 1127 a handful of times," I said. "How did you manage to learn her language in that time?"

"I didn't," Windboy said. "I let the wind speak for me. It can understand practically any speech, and translate in real time."

I was about to say something else, when I noticed the necklace the vendor woman was wearing. It was a jumble of mismatched stones and trinkets, but holding them all together were tiny strands of —

"Copper wire!" I perked. I walked up to her briskly, forgetting myself. As I got close, I caught the aroma of someone who hadn't showered or bathed in months. Oh yeah, that's right — soap hadn't come into common use yet. I pushed the thought aside. "Uh, 'scuse me, ma'am, can I ask you about your necklace?"

She looked at me in bewilderment, and said a couple of incomprehensible words.

"Oh," Windboy said. "I should tell the wind to translate for you, too."

Oops. Windboy gestured, and whispered "There you go," but my blunder had already been made. I addressed the vendor woman again, hoping Windboy's magic translator would work. "Sorry, ma'am, I accidentally reverted to my native language. Um, we're not from around here."

She folded her arms and said "I gathered that much."

This time, thankfully, I could understand her. The effect was rather eerie; I could see her mouth moving as though speaking another language, but the sound that reached my ears was perfectly normal (to me) 20th century English. I continued: "I was wondering if I could ask you about your necklace."

"It's not for sale," she said gruffly.

"Oh," I waved my hands, "I don't want — I mean, the little wires connecting the pieces. I'm looking for copper wire like that, but longer. Do you sell something like that?"

She shook her head testily. "Just what you see here."

"Then," I said, "Can you tell me who —"

"I got the necklace from a traveling merchant," she cut me off. I think she was getting fed up with me. "No, I don't know who, no, I don't know where they went, and no, I don't know anyone in town who sells copper wire. Now either buy something I have on display here, or leave me alone."

That could have gone better. I gave a quick glance at her display stand, then almost turned to leave when a tall roll of beige canvas caught my eye. It was knit tightly enough together that it could catch the wind. The wheels in my head started to turn. I asked her, "Can I buy this roll of canvas?"

"The whole roll?" she said. "You building a sailboat? If you want the whole roll, it'll cost you sixpence." She pointed sternly at me. "No haggling."

"Uh, okay!" I said, and unhitched my coin bag. It made enough of a jingling sound to attract the attention of a couple of bystanders. I counted coins as I handed them to her. "One, two, three, four, uh four-and-a-half, five, five-and-a-half, five-and-three-quarters, six."

She inspected the coins briefly, bit one of them to make sure it was real, and then indicated the canvas roll. "It's all yours."

"Thank you," I said, put my coin pouch away, and lifted the canvas roll. It was surprisingly heavy. I had to carry it upright, like I was doing a caber toss. I addressed Windboy. "Should we go to the inn now?"

"Yes," he said, and led the way.

I was a little more self-conscious now, with this long awkward roll of canvas in my arms. We seemed to be getting even more looks than before. We rounded a corner into a short alley between two small buildings, then turned another corner. The marketplace crowd was behind us and out of sight now. I wondered, was their extra attention really just because I was carrying the canvas like this, or was it because of the coins that I'd —

A man darted out right in front of us, brandishing a knife. "Hand over the purse," he demanded, "If you don't want to get hurt."

Windboy glared at him. "Don't hurt my friend." He jutted one arm out straight in front of himself, palm up, as if pushing someone away. At once, a single focused burst of wind shot forth and slammed into our would-be assailant like a pile driver. The man doubled over, flew ten feet backwards, and landed on his back.

He lay dazed for a couple seconds, then shook himself back into the moment and stared in terror at Windboy. "You're a warlock!" he shouted. He scrambled to his feet as best he could and dashed away.

I was mortified. "Oh no. Now he's going to tell the locals that we're witches!"

Windboy only smiled. "No he won't. If he accuses us of witchcraft, he'll have to tell them what I did. And in the unlikely event they believe him, it's going to be pretty obvious that it happened because he tried to rob us. He'd basically be turning himself in. And he knows it. He won't want to risk the penalty for theft."

I raised my eyebrows. "Hmm. Hadn't thought about it that way. I guess a superstitious fear of witches can't trump the real fear of jail time."

Windboy frowned. "Imprisonment for crimes is a 20th century luxury. The penalty for theft in 12th century England is getting your hand cut off."

Instinctively, I winced and clutched my right wrist. I almost dropped the canvas roll.

We walked on and soon found the inn. I let Windboy do the talking this time. He arranged a room for us, at a cost of "tuppence" for the night. It wasn't heated, the bed was stuffed with straw and probably had bugs in it, and the only table I might have a chance to use as a workbench wobbled unevenly. But at least the room had four walls and a roof, and a door we could close.

And, to be honest, I was a bit relieved to discover that even super heroes needed to go to the bathroom every once in a while. Though I worried about the logistics when my turn came. Not only had the flush toilet not been invented yet, neither had toilet paper. I'd have to find out first hand how the locals probably did their business. . . .

Thankfully, the two penny price for a night's lodging included a meal served in the communal hall at sundown. It wasn't much of a meal, though. We each had a bowl of some kind of gruel, which we ate with wooden spoons, and a warm mug of some kind of flat beer. It was quite bitter and definitely had a bit of alcohol in it. I worried briefly about the morality of letting a 10-year-old boy drink alcohol, but another family at a table nearby were letting their two even-younger children drink the same stuff. Maybe the alcohol acted as a preservative, and kept the drinks from spoiling or something.

After we'd retired back to our room, I started unrolling the canvas. I frowned, planning my next move. "I'm also going to need some wooden sticks, some nails or other fasteners, maybe some glue, and a good length of thin rope. I'd prefer scissors to do the cutting, but I can get by with just a sharp knife. I just hope I can find all the parts I need in town."

Windboy puzzled. "You need canvas and wood to make a radio detector?"

"No," I said. "This isn't for the radio detector. You heard the vendor say there's no copper wire in town? That means we're going to have to look elsewhere, and that means more flying. If you're going to be knocking me into the sky and tossing me around with wind, I'm going to give myself at least some semblance of airborne control."

I paused for emphasis. "I'm gonna build a hang glider."